India’s Push for Electronics Self-Reliance: Navigating the China Dependency and Global Trade Shifts

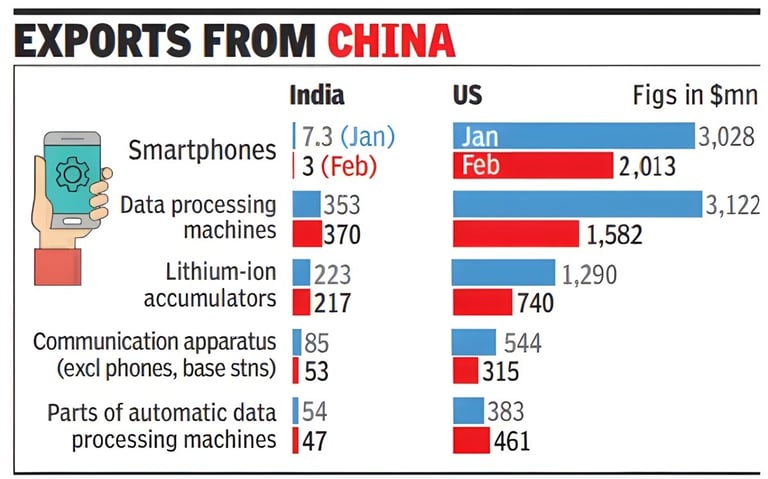

India stands at a critical juncture in its economic journey, balancing its ambition to become a global manufacturing powerhouse with its heavy reliance on Chinese electronics imports. Recent data indicates a decline in electronics exports from China to India and the United States in early 2025, signaling a potential shift in global trade dynamics.

5/5/20256 min read

India stands at a critical juncture in its economic journey, balancing its ambition to become a global manufacturing powerhouse with its heavy reliance on Chinese electronics imports. Recent data indicates a decline in electronics exports from China to India and the United States in early 2025, signaling a potential shift in global trade dynamics. This trend, coupled with escalating U.S.-China trade tensions and India’s proactive policies like the Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme, presents both challenges and opportunities. As India aims to reduce its trade deficit with China—nearing $100 billion—and bolster domestic production, the question arises: Can India achieve electronics self-reliance while navigating complex global supply chains? This article explores India’s strategic push, the hurdles of dependency on China, and the global trade shifts shaping its future.

The Context: India’s Electronics Dependency on China

India’s electronics sector has long been tethered to China, which supplies over 40% of its electronic goods, including critical components like integrated circuits, displays, and batteries. In FY24, India imported $89.8 billion worth of electronics, with 44% sourced from China and 56% when including Hong Kong. This dependency stems from China’s dominance as the world’s manufacturing hub, offering scale, cost-efficiency, and advanced technology that few can match. For instance, imports of integrated circuits surged from $166.1 million (2007–2019) to $4.2 billion (2020–2022), with China’s share rising to 67.5%.

However, this reliance has economic and strategic implications. India’s trade deficit with China widened to $99.2 billion in FY25, driven by electronics and components. Geopolitical tensions, including the 2020 Galwan clash, have further complicated the relationship, prompting India to tighten scrutiny of Chinese investments and imports. The government’s “Make in India” campaign and PLI schemes aim to reduce this dependency by fostering domestic manufacturing, but the transition is fraught with challenges.

The Decline in Chinese Electronics Exports: A Window of Opportunity?

Recent data from early 2025 shows a drop in China’s electronics exports to India and the U.S., attributed to U.S. tariffs as high as 245% and India’s increasing import restrictions. This decline aligns with global supply chain shifts, as companies like Apple, Foxconn, and Walmart diversify production to countries like India and Vietnam. Apple, for instance, now produces one in five iPhones globally in India, with exports reaching $17.4 billion in FY25. This pivot is driven by both geopolitical risks and economic incentives, such as India’s $2.7 billion in electronics manufacturing subsidies.

The decline in Chinese exports offers India a chance to capture a larger share of global electronics production. The Indian Cellular and Electronics Association (ICEA) estimates that Indian electronics exports, including smartphones and laptops, are now 20% cheaper than Chinese counterparts in the U.S. market due to tariff exemptions. This cost advantage, combined with India’s growing manufacturing ecosystem, positions it as a viable alternative to China. However, scaling up production to meet global demand requires overcoming significant hurdles.

India’s Strategic Push: PLI and “Make in India”

The Indian government’s flagship PLI scheme, launched in 2020, is a cornerstone of its self-reliance strategy. With an outlay of Rs 1.97 lakh crore across 14 sectors, including electronics, the scheme incentivizes domestic production and export growth. In FY23, electronics exports surged 2.3 times compared to FY21, with investments in the sector rising to Rs 2.63 lakh crore. Companies like Dixon Technologies and Samsung have expanded operations, with Dixon’s million-square-foot plant employing 26,000 workers and Samsung producing 120 million phones annually.

The PLI scheme has also spurred component manufacturing, a critical gap in India’s electronics ecosystem. The government aims to source $20 billion in IT hardware components locally by 2027, reducing reliance on Chinese imports. Additionally, anti-dumping probes into Chinese solar cells and mobile phone components signal a protective stance to shield domestic industries from cheap imports.

Yet, challenges persist. India’s manufacturing sector accounts for only 13% of its economy, compared to China’s 25%. Skilled labor shortages, inadequate infrastructure, and dependence on imported raw materials hinder progress. For instance, Vikram Bathla of LiKraft noted that most machinery and inputs for battery production are still imported from China, underscoring the difficulty of achieving full self-reliance.

Global Trade Shifts: The U.S.-China Trade War and India’s Role

The intensifying U.S.-China trade war, marked by tariffs of up to 245% on Chinese goods, has disrupted global supply chains and created opportunities for India. U.S. firms are seeking alternatives to China, with India emerging as a key beneficiary. Walmart, for example, increased its U.S. imports from India to 25% in 2023, up from 2% in 2018, while reducing China’s share to 60%. Similarly, Chinese firms like Haier are adapting to India’s terms, with Haier negotiating to sell a 51–55% stake in its Indian operations to comply with local regulations.

India’s low exposure to U.S. trade (2.7% of American imports compared to China’s 14%) shields it from direct tariff fallout, while its growing production capacity attracts global players. The government is engaging U.S. firms exiting China and supporting Indian companies in sectors like electronics, pharmaceuticals, and toys. Exports to the U.S. rose 11.6% to $86.5 billion last year, even as smartphone imports from China dropped 70%.

However, the trade war also poses risks. A flood of Chinese goods into global markets, dubbed “China Shock 2.0,” threatens Indian industries like textiles, where local producers struggle against cheap imports. Anti-dumping measures and tariffs of 12–30% on Chinese steel imports reflect India’s efforts to protect its market, but balancing openness to global trade with domestic priorities remains complex.

Challenges to Self-Reliance

Despite progress, India’s path to electronics self-reliance is riddled with obstacles:

Component Dependency: India lacks the ecosystem for high-grade raw materials and components like displays and batteries, which require Chinese expertise. Industry executives estimate a $75–80 billion demand for components by 2026, necessitating Chinese technology transfers.

Skilled Workforce: The shortage of skilled workers limits India’s ability to operate advanced manufacturing facilities. Training programs and technology transfers from countries like China, Korea, and Taiwan are critical.

Supply Chain Risks: Quality control orders on base metals, intended to curb substandard imports, have inadvertently disrupted electronics supply chains, highlighting the need for sector-specific exemptions.

Geopolitical Tensions: While India remains open to Chinese investments in non-sensitive sectors like solar panels, national security concerns and past border clashes complicate collaboration. Visa delays for Chinese executives have cost the industry $15 billion in production losses since 2020.

Global Competition: Countries like Vietnam and Mexico are also vying for supply chain shifts, leveraging their proximity to the U.S. and established manufacturing bases. India must act swiftly to maintain its edge.

Opportunities and the Road Ahead

India’s electronics sector is poised for growth, driven by favorable policies, global trade realignments, and a burgeoning domestic market. Apple’s $8 billion in smartphone sales in India, despite an 8% market share, underscores the potential of its middle class. Foxconn’s planned 300-acre facility in Uttar Pradesh and Tata Electronics’ $612 million in iPhone exports signal robust investment.

To capitalize on these opportunities, India must:

Enhance Component Manufacturing: Expand PLI schemes to cover sub-assemblies and raw materials, encouraging joint ventures with Chinese firms for technology transfer under strict terms (e.g., limiting equity to 10%).

Build Skilled Talent: Partner with global tech leaders to train workers in advanced manufacturing techniques, addressing the skill gap.

Streamline Regulations: Exempt electronics from broad quality control orders and expedite visa processes for foreign executives to boost production efficiency.

Leverage Trade Agreements: Strengthen trade talks with the U.S. and EU to secure low-tariff routes for Indian exports, positioning India as a backdoor to Western markets.

Invest in R&D: Foster innovation in electronics design and semiconductor production to reduce reliance on imported technology.

Conclusion

India’s quest for electronics self-reliance is a high-stakes endeavor, blending economic ambition with geopolitical strategy. The decline in Chinese electronics exports, coupled with U.S.-China trade tensions, offers a rare window to reshape global supply chains in India’s favor. However, overcoming dependency on Chinese components, building a skilled workforce, and navigating trade complexities require sustained effort. The PLI scheme and “Make in India” have laid a strong foundation, but India must act decisively to transform challenges into opportunities. As the world watches, India’s ability to balance openness to global trade with domestic priorities will determine its place in the electronics manufacturing landscape. The journey to self-reliance is long, but with strategic focus, India could emerge as a global leader in the decade ahead.

References

Times of India, “Eyes on Electronics Imports from China,” May 4, 2025.

Times of India, “Donald Trump Tariffs Push Chinese Giants to Bow to India’s Terms,” April 21, 2025.

Times of India, “Most US iPhones to Be ‘Sourced’ in India, Says Apple CEO,” May 1, 2025.

The Economic Times, “Move to Protect Against Cheap Imports Hurts Electronics Inc,” April 18, 2025.

Times of India, “The $22 Billion Pivot: Apple’s India Gamble Starts to Pay Off,” April 13, 2025.

Posts on X, reflecting sentiment on India’s electronics import dependency and Chinese investments.