Transform Your Ideas Into Reality Faster through our Expert Electronics Manufacturing Solutions

Trusted by startups and inventors

★ ★ ★ ★ ★

Expert Electronic Manufacturing Services & NPI for Startups, Inventors, Innovators

Transform Your Ideas into Reality Faster with Our NPI Services

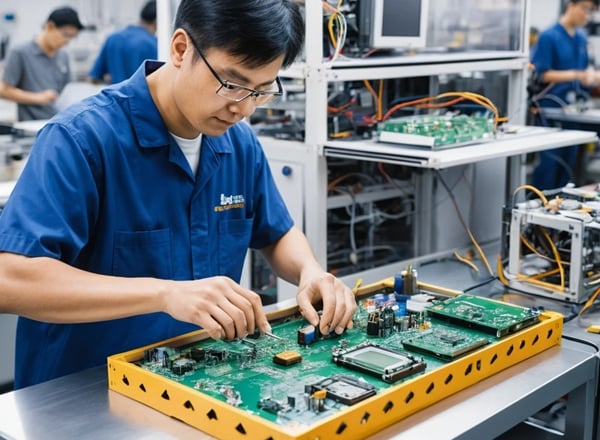

Accelerate your electronics product innovation and launch through our all-around services in product development, prototyping, plastic molding, metal fabrication, and electronics manufacturing.

Support startups, inventors, and small businesses from concept to market with expert electronic manufacturing services — your behind-the-scenes partner for concept-to-market success.

Tap into our 15 years of cross-disciplinary expertise in electronics manufacturing services, backed by powerful production advantages in China.

• Cost-effective production solutions

• Established manufacturing networks

• Deep understanding of Western/Chinese business practices

• Comprehensive supply chain optimization

150+

15

Trusted by Startups

Expert Solutions

Comprehesive Electronics Manufacturing Services

High-quality plastic injection molding and enclosure manufacturing for industries like consumer electronics, automotive, and medical devices. Whether you need custom prototypes or low-volume production, our expert electronic manufacturing services deliver precision, speed, and cost-effectiveness.

Precision metal fabrication and CNC machining for structures, sheet metal parts, heatsinks, fastenings or connectors. Custom metal parts with tight tolerances and outstanding durability meet the toughest standards.

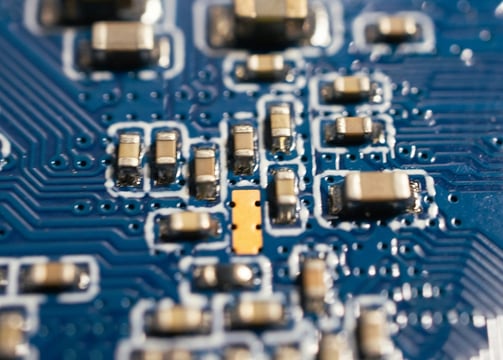

Seamless electronic prototyping and PCB assembly for new product development and production. From strategic Bill of Materials (BOM) sourcing to precision SMT and THT assembly, we deliver end-to-end electronic manufacturing services tailored to your needs.

Trust our advanced capabilities to transform your concepts into reliable, market-ready solutions with unmatched efficiency.

Peakingtech is incredible! They helped me launch StudioBox, expertly handling everything from screen selection and circuit design to metal hinges and plastic molding. Their dedication and skill made the entire process seamless. Highly recommended for inventors!

★ ★ ★ ★ ★

Testimonial

Electronic Manufacturing Services & Proven Experience

Delivering Precision, Capability, and Innovation in Electronic Manufacturing.

Our Four Pillars of Electronic Manufacturing Expertise